1.970x10-5

1.965x10-5

1.960x10-5

1.955x10-5

1.950x10-5

25

20

15

10

5

0

Temperature (C)

Figure 14. Molar volume of hexagonal ice under 1 atm pressure at temper-

atures near its melting point.

and

c 1

1

*

Tf

Cp,H 2O(cr,I)

∫

dT = a[ln(Tf ) - ln(Trw )] + b(Tf - Trw ) -

2 - 2 .

(52)

T

2 Tf Trw

Trw

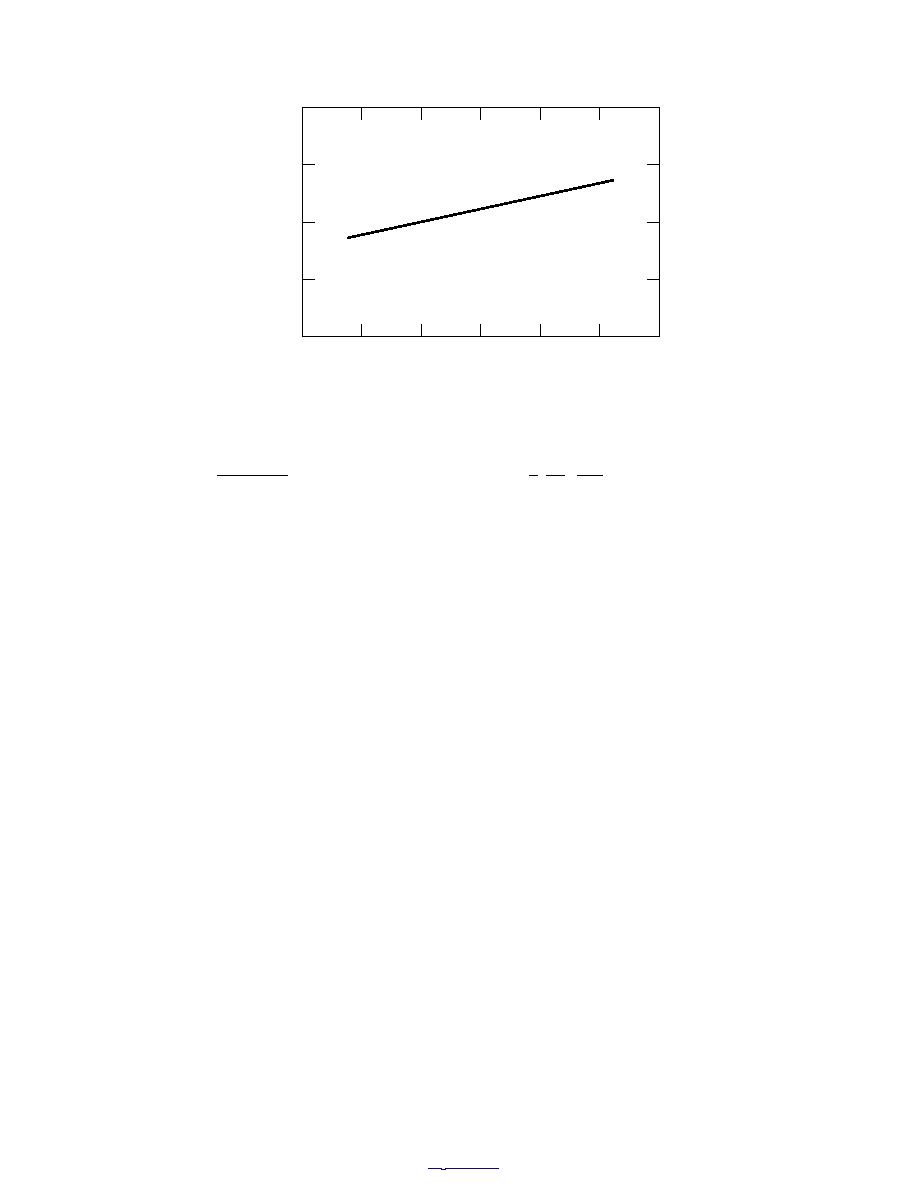

Molar volume

Water is one of the few substances for which one of its solid phases is less dense than its

liquid. The molar volumes of hexagonal ice, the phase most commonly encountered in

nature, at temperatures near its melting point are presented in Figure 14.

PHYSICS OF FROZEN POROUS MEDIA

Moderately cool temperatures affect the physicalchemical state of water and its pro-

pensity to flow through porous media. For contaminant transport, changing temperatures

affect the chemical potentials of the solvents and solutes in the pore solutions and therefore the

solubility and reactivity of the solutes. These changes in the physical properties of the sol-

vent and chemical properties of the solutes can affect dramatically the mobility of contam-

inants in cold regions.

At cold temperatures, at which surficial, vadose, and aquifer waters freeze, the nature of

flow changes dramatically. First, at a macroscopic level, because the effective volume of

voids is reduced, ground has a much lower permeability when frozen. This affects the ba-

sin-scale hydrology in cold regions in sometimes unpredictable ways.

Second, while frozen ground is less permeable, it is not impermeable. The mathematical

description of transport of solutes through frozen ground is inherently more complex than

unfrozen ground for the following reasons:

1. The solvent, water, is partitioned into two phases, liquid water and ice, that are inti-

mately commingled in the pores of the ground.

2. As the ice forms, the solutes (including the contaminants) are largely excluded from

the ice, concentrating the remaining liquid-water solutions in a thin film at the colloid

surfaces. The chemical potentials of the solutes in these solutions, used to estimate the

effects of solutesolute and solutesurface interactions are not understood well enough to be

modeled accurately.

3. In unfrozen coarse-grained soils, the movement of solutes is controlled by the Darcian

flow of water in response to gravitational and pressure gradients. In frozen ground, solutes

may also move appreciably in response to thermal and osmotic gradients--transport

mechanisms that are less well understood and more difficult to parameterize than flow in

response to gravitational and pressure gradients.

19

TO CONTENTS

Previous Page

Previous Page